|

|

|

Playboy

October, 1995

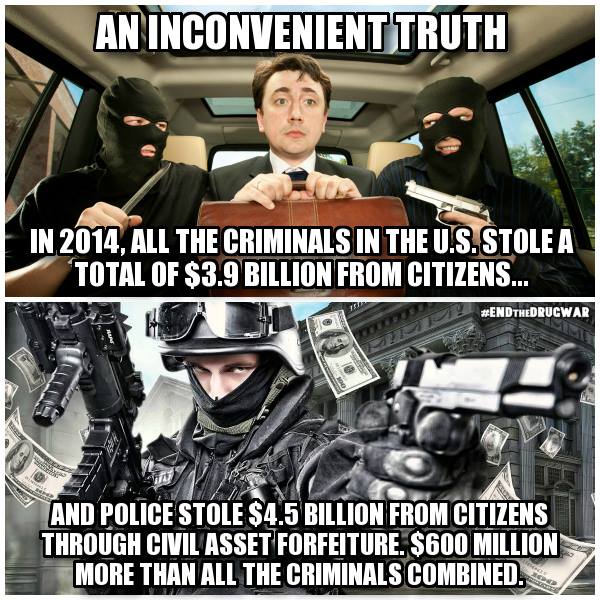

HEADLINE: Uncle Sam wants your stuff: is asset

forfeiture another term for theft? federal law enforcement;

The Playboy Forum

BYLINE: Bovard, James

Early on the morning of October 2, 1992, 31

people from eight law enforcement agencies barged into 61-year-old

Donald Scott's home on his 200-acre Malibu ranch. Scott's wife

screamed when she saw the intruders. When Scott came out of

the bedroom with a gun, Los Angeles County Sheriff's Deputy

Gary Spencer shot him dead. Agents then searched his home and

property.

When asked to defend the raid, the sheriff's

deputy said that a confidential informant had told him that

Scott's wife liked to flash $100 bills; another had told him

that there were 4000 marijuana plants growing on the property.

Finally, an agent from the Drug Enforcement Administration flew

over the property and swore he saw 50 plants. On the basis of

this information, the sheriff's department obtained a warrant.

The 31 agents searched for hours but failed

to find any illicit drugs. Scott's death was ruled a "justified

shooting." The agents were deemed to have acted in good

faith on bad information. It was all constitutional.

That was the official story. However, after

a five-month investigation, a report by Ventura County District

Attorney Michael Bradbury's orifice concluded that "the

Los Angeles County sheriff's department was motivated, at least

in part, by a desire to seize and forfeit the ranch for the

government." The sheriff's deputy, the report said, had

fabricated evidence to get the search warrant that "became

Donald Scott's death warrant." The raid was a land grab,

pure and simple.

Bradbury revealed that at a briefing before

the raid, government agents were informed that the ranch had

been appraised at $5 million. During the raid, a DEA agent carried

a map that noted the value of adjacent properties. A deputy

told a National Park Service ranger that if the DEA could find

as few as 14 marijuana plants, the government could seize the entire property.

According to a family friend, the Park Service

had repeatedly tried to buy Scott's land, intending to use the

property as an annex to an existing park. Some observers believe

that the sheriff's department planned to seize the property

and then sell it at considerable profit to the Park Service.

Bradbury's report launched congressional hearings,

lawsuits and impassioned editorials.

How did the land of the free get into such a mess?

In 1789 the first Congress passed a law allowing

the government to seize the property of pirates and smugglers

who sought to evade tariffs. The founding fathers were cautious,

however, because of their experience with British colonial governors

who had the nasty habit of confiscating property without cause.

The new government argued that it could seize a pirate's ship

or, in one case in 1814, a cargo of contraband coffee beans,

because ships and bags of coffee had no constitutional rights.

But citizens did. Offshore, the government played by one set

of rules. Onshore, property rights were often considered to be sacred.

Twenty-five years ago, the remnants of that

reverence disappeared, one of the first victims of the war on drugs.

In 1970 Congress enacted legislation to permit

the seizure of property of Mafia organizations and major drug

smugglers. The logic behind the law was politically correct:

Felons should not be allowed to keep the spoils

of criminal activity. The tools of the trade--ships, planes,

guns, drug labs--should not be returned to the hands of organized

crime for later use. But the Racketeer Influenced Corrupt Organization

statutes spread like a virus, and federal agents can now seize

private property under 200 different statutes. Since 1985 federal

seizures of property under forfeiture laws have increased by

1500 percent and now total almost $4 billion.

The RICO virus, with its promise of a new

revenue source for cash-strapped agencies, touches every level

of government. According to one source, state and local governments

have increased their confiscations of private property by a

hundredfold in the past decade.

The legal language in seizure cases still

holds to its early form: U.S. Government vs. 1994 Mercedes-Benz

is the tide of one seizure case; The United States of America

vs. Twelve Thousand Three Hundred Ninety Dollars is another.

But the naming of inanimate property hides the assaults on individuals.

The government loves asset forfeiture because it gets to play

by new rules. Suspicion of criminal activity is all it takes

to launch a raid. Tossed out the window are probable cause,

the presumption of innocence and the right to a speedy trial.

The government doesn't have to prove anything--the victim of

a seizure does.

Close to 80 percent of the people whose property

is seized by federal agents are never charged with a crime.

Many agents use forfeiture laws to pillage, often acting on

trivial or false charges. Forget the original targets-drug cartels

and the Cosa Nostra. Police now regularly seize the cars of

johns, the bikes of graffiti artists, the tractors used by farmers,

the life savings of the elderly and more:

* Customs officials confiscated the $250,000

yacht of Willem Eickholt, a Dutchman living in Washington State.

His crime? He had sailed to Cuba and given away 15 cartons of

dried milk and other care packages to a Cuban organization that

feeds the hungry.

Customs officials threatened to charge Eickholt

with violating the Trading With the Enemy Act.

* In Augusta, Georgia the FBI seized three

Mercedes-Benzes from a businesswoman after alleging that her

husband had placed sports bets on her car phones.

* In Ottsville, Pennsylvania, police seized

the $250,000 home of Richard and Bonnie Nightingale after officers

found marijuana plants inside. The Nightingales and their three

children were evicted. Deputy District Attorney Gary Gambardella

observed: "People say that selling drugs is a victimless

crime, but the children are the real losers here."

* New Jersey police confiscated a woman's

1987 Oldsmobile after they alleged that her son had used it

to drive to a store where he then shoplifted a pair of pants.

* Federal prosecutors in Pittsburgh nearly

destroyed Anna Ward after she had fully cooperated with them

in their attempt to solve the murder of her husband, Darryl

Ward. Prosecutors decided that Darryl Ward had been a drug dealer

and that all of his previous income was drug-related. They confiscated

almost all of Anna Ward's assets (she had her own legitimate

business), including the family's furniture. Prosecutors even

sought to confiscate the proceeds of her husband's life insurance.

Anna Ward and her three children were forced to go on welfare.

* In Utah police seized the 160-acre ranch

of Bradshaw Bowman after police found a handful of marijuana

plants growing on his property, far from his house. Eighty-yearold

Bowman told The Pittsburgh Press: "I've had this property

for almost 20 years, and it's absolute heaven. My wife is buried

here. I didn't even know the stuff was growing there."

Perhaps you think the war on drugs is a noble

enterprise, that the feds' "take no prisoners--only property"

approach is fine. If so, hold on to your wallet: * In July 1992 several Cleveland landlords

informed the police of drug dealing in their buildings. The

city responded by seizing the buildings and evicting all tenants,

even when the dealing occurred in a single apartment.

* The owner of a 36-unit apartment building

in Milwaukee evicted ten tenants suspected of drug use. To further

help eradicate the drug problem, he gave a master key to beat

cops, forwarded tips to the police and hired two security firms

to patrol the building. The city still seized his building.

Why? It wanted the landlord to evict all tenants and leave the

building vacant for a number of months. The landlord didn't

want to bankrupt himself. But it was cheaper for the cops to

seize the building and empty it rather than to engage in police

work at the site.

Often, forfeitures are based on the word of

confidential informants, many of whom are ex-convicts or people

avoiding conviction by cooperating with police. Confidential

informants are given as much as 25 percent (up to $250,000)

of the value of any property that agents seize as a result of

their leads. A worse set of incentives would be hard to imagine.

A paid informant in Adair County, Missouri told police that

Sheri and Matthew Farrell were processing "marijuana for

sale" on their 60-acre farm, and the government seized

the property. The informant later refused to testify in court--first

claiming illness, then loss of memory. Federal prosecutors dropped

the charges against the Farrells, who got their land back only

after agreeing not to sue the government for damages.

What happens to the valuables that government

agents grab from citizens?

Many police agencies keep all or most of what

they seize, sometimes using the money to buy exercise equipment,

expensive cars, gold watches and, in one case, to pay the settlement

in a sexual harassment suit. In Nueces County, Texas, Sheriff

James Hickey used assets from a federal drug forfeiture fund

to grant himself a retroactive $48,000 raise just before he

left office.

Asset forfeiture also encourages police theft.

Last year, 26 members of the elite narcotics squad of the Los

Angeles County police department were convicted of stealing

money from drug suspects. Some defended their behavior, claiming

that since the government was allowed to steal money, why couldn't

the cops do the same? County Sheriff Sherman Block said, "I

don't know how you can draw an analogy between the asset forfeiture

program, which is a matter of law, and helping yourself to what's

available." Unfortunately, because forfeiture laws are

so vague and expansive, there may be little difference.

Accounting for forfeiture funds is sometimes

incredibly sloppy. An investigation by the General Accounting

Office discovered that the Customs Service had arbitrarily made

a $6.4 million deduction to its forfeiture fund in order to

make its books appear balanced and to "account" for

missing cash.

In 1993 Representatives Henry Hyde (R-Ill.)

and John Conyers (D-Mich.) both proposed bills to limit the

government's asset seizure powers. Neither passed. In June Hyde

again introduced a Civil Asset Forfeiture Reform Act, which

is endorsed by the National Association of Criminal Lawyers

and the ACLU.

Many civil libertarians believed that the

Clinton administration would correct some of the more overt

abuses of asset forfeiture. Attorney General Janet Reno, however,

has continually postponed substantive reform. The federal courts

have ruled that asset seizures can sometimes violate the Eighth

Amendment's prohibition on "excessive" fines. Such

was the case of the South Dakota man whose car-repair business

and mobile home were confiscated after he sold two grams of

cocaine to an undercover agent. A federal appeals court recently

ruled that asset forfeiture can violate double jeopardy provisions

because the defendant is punished twice--once through the seizure

of his property by administrative means and a second time through

a criminal trial. In 1992 the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals

complained that it was "troubled by the government's view

that any property, whether it be a hobo's hovel or the Empire

State Building, can be seized by the government because the

owner, regardless of a criminal record, engages in a single

drug transaction."

The courts may be troubled, but the rulings

so far have done little to deter enthusiasm for the practice.

In January the mayor of Helper, Utah, Mike

Dalpiaz, announced that police officers would be permitted to

keep up to 25 percent of all the property or cash they confiscate

from suspected drug dealers. Dalpiaz explained the program's

rationale: "Why not give our guys a reason to be more aggressive?

This doesn't cost the city a thing; it's a wash. If the city

gets a house through a drug forfeiture, and we put it on the

market and sell it for $50,000, then, by God, the guy who made

the bust is going to get a nice bonus."

A concept that was intended to punish pirates

has created a nation of pirate police. When greed and a lust

for spoils become the engine of law enforcement, what happens

to justice?

Editor's note: In June the Supreme Court agreed

to hear a case on asset forfeiture where police seized a car

used by a married man arrested for soliciting a prostitute.

The wife, an innocent party, claims that the seizure violated

her right of due process.!

James Bovard is author of "Shakedown:

How the Government Screws You From A to Z."

FEAR (Forfeiture Endangers American's Rights)

Spider Bait transporting dazed and confused free range arachnids to insane asylums since MVM

ward marijuana recipes cooking heating weeds grass skunk smoking

quiff squabble mojo rising 8k.com feedreeder 8k race run ganja eclectic jazz

ours Walking extra meat Virginia brad forbidden truth summer solstice

Lost as a blind eagle government constitutional Convention cell phones spirits health care maple goddess clean water

Homeland security cannabis apples spies space ghost peace love and tolerance blueberries